FACTS

Cancellation of the Hungarian part of the International mark No. 589.425 „Original grosser Schweden bitter” registered on July 24, 1992 in classes 5 and 33 has been requested.

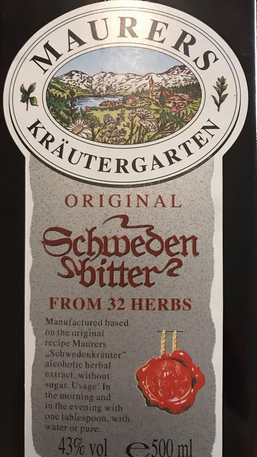

The applicant of the cancellation request referred to his marks „MAURERS Schweden bitter”

and „Abtei Schweden bitter”, not registered, but used in Hungary since 1991, before the attacked International mark was filed. Moreover, he said that the attacked mark was filed in bad faith.

The Hungarian Intellectual Property Office (HIPO) cancelled the Hungarian part of the international mark. It was held that the attacked mark is confusingly similar to „MAURERS Schweden bitter” mark. The latter had been used since 1990 for similar goods. However, the bad faith of the owner of the mark to be cancelled was not proven.

The owner of the cancelled mark requested review with the Metropolitan Tribunal but this appeal request was refused. The Tribunal stated that the applicant of the cancellation request had used the signs „MAURERS Schweden bitter” and „Abtei Schweden bitter” on the Hungarian market before the filing of the international mark „Original grosser Schweden bitter”. In the cancelled international mark the term “original” modifies only slightly the known term “Schweden bitter” which is the dominant element of the conflicting marks.

Moreover, the mark of the applicant for cancellation, namely „MAURERS Schweden bitter signifies also the generally used name of the product. This term is graphically, specifically elaborated and as such, captures the attention. Moreover, the term „MAURERS Schweden bitter” is presented in similar and characteristic letters as the later IR mark. As a result, customers may use the term “Schweden bitter” for the identification of the goods. The dominant elements of the conflicting marks are identical, therefore confusion cannot be excluded.

The same is valid in respect of the device elements of the conflicting marks.

The term “Schweden bitter” is represented by similar letters and the same old style. It is not relevant that before the priority date similar signs of third parties had been on the market. The confusion is no more excluded by the fact that the applicant of the cancellation had used his mark on the market before the priority date of the attacked mark.

The claimant of the cancellation filed an appeal with the Supreme Court but this was also rejected. The court said that when the confusion of two marks is to be examined, where there are such dominant elements that assure confusion between the marks, the likelihood of confusion cannot be excluded. The appellant was not right saying that in respect of a mark combined with a word and device the device element is also decisive. The court said that on the contrary, when comparing the combined conflicting marks the dominant element was “Schweden bitter”. The elements of the attacked signs „MAURERS Schweden bitter” and „Abtei Schweden bitter” are presented in similar characters. These cannot be considered as distinctive elements. The Tribunal was also right holding that in the mark of the Appellant the term “Original” modifies only slightly the meaning of the term “Schweden bitter” and the consumers consider the dominant element of the good is “Schweden bitter”. The Court said that there was a likelihood of confusion and the attacked mark ought to be cancelled.

(Pkf.IV.26.055/1999)

Comments

The question of likelihood of confusion is often the hardcore point of the litigation on cancellation or infringement of the mark.

The Doctrine on dominant element is often helpful but not always.

In the above reported case the marks with word and device elements were to be examined and compared. The three instances held that the word element “Schweden bitter” was dominant and distinctive. But they had to examine also the device elements, which, in conformity with the case law, have a secondary importance compared to the word element.

In this respect the conclusion was convincing. Let us observe that only a very characteristic device element could assure the distinctiveness of the mark.

Though all instances were aware that the dominant element of the marks were the words “Schweden bitter”, which was the name of the product, they did not consider this fact as non-distinctive probably as the term “Schweden bitter” was then not yet a generally known product name attributable to any of the parties and known by the general public. This property was not proven by the cancellation applicant. I believe that this negative behaviour of the three instances, namely not dealing with a not proven well-known character of the name of goods “Schweden bitter” cannot be contested.

Such a procedural solution is not new, the rule for the Roman Praetor (judge) was already “ne eat iudex ultra et extra petita partium”, i.e. the judge has no right to go beyond the claim.

Final observation

The above reported case is in conformity with the actual Trademark Act (1997). As the system of the jurisdiction was reformed in 2003, today the appeal in similar cases would be judged by the Metropolitan Court of Appeal and not by the Supreme Court.

In-house Counsel

Doctor of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

Partner